Note: DACA recipients’ names have been changed to protect their identities.

The thrill of being granted DACA protection — the freedom to get a driver’s license, to be eligible for authorized employment, to pay in-state college tuition — might only be overshadowed by the ever-present fear of losing it. On this tenth anniversary of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) — which provides temporary permission to stay in the country to qualifying young adults brought here as children — two young women who completed their DACA applications with the assistance of Catholic Charities shared the ways their lives have been changed for the better by the stopgap federal policy, as well as the ways it has left them in perpetual limbo.

“I think I realized early on” about my status, said Anna, who came to the U.S. from Peru as a 5-year-old. Now 23 with a newly minted degree in global affairs/international relations and working for a nonprofit, she and her brother, who also has DACA — recipients and other young immigrants are often called “Dreamers” — are the first in their family to graduate from college. “Everyone was very happy for me. It had been a long journey.”

Although she applied for and received DACA when she was 15, Anna’s college years coincided with the Trump administration’s 2017 decision to revoke it; the subsequent legal wrangling over the policy was enough to derail her hopes of studying abroad. DACA recipients are allowed to travel internationally only under three conditions: education, humanitarian (illness of family member) or work, and no new DACA applications are being processed.

“Even though I’m able to do that now, unfortunately the time has passed for me to study abroad as a college student,” said the Northern Virginia resident, who paid for college with a combination of work, scholarships and help from her parents; non-citizens are ineligible for federal financial aid. Together, it was enough to afford in-state tuition at a state school and make Anna’s dream of earning a degree a reality.

Nina applied for DACA when she was 22 and working her way through community college after completing high school with honors.

“Once I graduated, it was, okay, how do we pay for school?” she said, recalling that her high school guidance counselor, unaware of her immigration status, suggested it might be cheaper to attend college in Bolivia, a country she left when she was 8 years old.

It took Nina, now 30, about four years, paying out of pocket, to earn an Associate’s degree, intermittently dropping out to work at a fast-food restaurant. With a younger brother who was also born in Bolivia, and a much younger sister born in the U.S., Nina felt a heavy responsibility to consider their futures, as well.

When she heard about DACA, Nina said, “I cried.” No longer would she have to ask for rides from friends or take on extra babysitting jobs. Now she could apply for a driver’s license, as well as scholarships and in-state tuition. Nina graduated with a BS in business management and now works for a Northern Virginia mortgage company.

Still, she said, “It’s always on my mind, because DACA is a temporary action.” She and her brother, who live at home with their parents and 10-year-old sister, “are basically their retirement,” since their parents are undocumented with no path to citizenship.

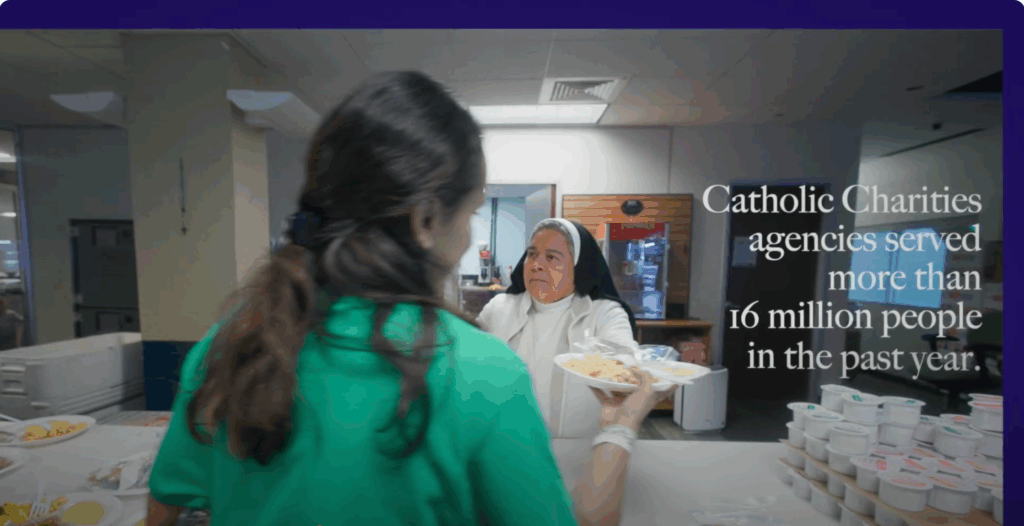

Both women were shepherded through the DACA application process — which involves considerable legal paperwork, and for which recipients must reapply every two years — by immigration legal services staff at their local Catholic Charities agencies.

Nina was one of the first to be helped by the staff when she applied. “The lawyer said be patient. We’re still navigating the process” on our end, she recalled. She’d heard about Catholic Charities through her parish.

For Anna, it was her mother who learned that Catholic Charities could help them apply, which “took a lot of pressure off of our shoulders,” she said. “We didn’t want to take the risk of messing anything up.”

The Catholic Charities staff has also helped Anna with renewals and with any problems she’s had in the administration of the program, always making themselves available to answer questions. Although both women express gratitude for the program and the help they’ve received in navigating it, uncertainty remains.

I’m aware that it’s not enough and it’s always in a state of contingency, a state of vulnerability,” said Anna. “There has to be another solution or a pathway to citizenship. It’s hard knowing that this can go away at any point.

For Nina, who said she and her brother are living out their parents’ “American dream” for their children, the possibility of losing it is ever-present and seems profoundly unfair.

“It’s always on my mind, because DACA is a temporary action. I really believe that we need something that’s fixed for us,” said Nina, adding, “I’ve been here all of my life. I grew up here. This is my country.”

Join Catholic Charities USA in urging Congress to pass the American Dream and Promise Act (H.R. 16) or similar legislation to provide permanent status and a pathway to citizenship for all Dreamers.