On the last day of March in 1980, as the sun disappeared slowly over San Salvador and the curfew that had been established by the junta a year earlier took effect once again, residents in the city prepared for another long night without electricity or running water. Some families listened to battery-powered radios that offered a diversion from the gunfire and explosions that pierced the air outside. Parents and children huddled together within the concrete foundations of their homes for fear of stray bullets that ripped through the wooden walls of the upper floors. The unrest in El Salvador was increasing.

Just a week earlier on March 24, in the same city, Archbishop Oscar Romero was assassinated as he celebrated Mass in the chapel of the Divine Providence Hospital. The day before he had denounced powerfully the military-government’s death squads, and he told soldiers to obey God rather than the officers who gave orders to shoot civilians. Since the government was supported by the rich landowners of El Salvador, it sought to snuff out the guerrilla groups that were calling for reform in the social and economic arenas (these groups would eventually coalesce into the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front, or FMLN). Anyone perceived to give aid and comfort to the guerrillas was also eliminated. Archbishop Romero was caught in the middle, trying to protect the ordinary people who also felt pressed in by both sides of the conflict.

The funeral for Archbishop Romero was held on March 30, and, tragically, government troops began shooting at the large crowd of mourners who had gathered outside the Metropolitan Cathedral, causing the deaths of at least 30 people (75,000 lives would be lost by war’s end in 1992). Less than a mile away, at the house that sat at 1434 Avenida Espana, Wil Alveno (now the database manager for CCUSA) had just welcomed back his girlfriend, Marina, who had left the funeral early because she was overcome with a foreboding sense of fear. Her premonition was confirmed as they heard the booming sound of bombs and the uproar of the crowd, knowing immediately where the tumult was coming from. They went quickly to the roof of the house and saw the billowing smoke clouds rising from the direction of the cathedral. They had no idea that the very next day Wil’s family would be touched by the growing violence as well.

San Salvador was not always like this. Wil, who was born in 1965, remembers the first decade of his childhood as mostly peaceful. When he was seven, Wil would play soccer with his siblings in the streets or sit in the park that was catty-corner from their home. Wil’s father worked as a salesman for an English mimeograph company, and his mother ran a cafeteria from the ground floor of their house. Since Wil was born an Albino, he could not be outside for long periods and, therefore, would often sit at the door of the cafeteria selling candy to customers from a basket his mother had prepared for him. Some of these customers worked across the Avenida Espana at the office of the Democratic Nationalist Union party (UDN). Wil remembers that, listening to these gentlemen talk, “I always heard information about what was going on.”

By 1972, however, no one in San Salvador, even children, needed anyone to point out the goings-on. “You would go to school and then, coming home, you would see people in the streets,” Wil recalls. “People having a meeting, people marching, going downtown. And it never ended good: people were rowdy, some were armed, and sometimes it ended in violence.” In February of 1972, the people in the streets protested what they thought was a rigged election by the army, which denied Jose Duarte the presidency (Duarte was exiled to Guatemala, but he escaped to Venezuela for seven years before returning to El Salvador).

Still, most of the time, Wil’s days were filled with school and family life. The “struggle,” as Will calls it, remained in the realm of adults and would present itself to him only indirectly: “My mother used to drag me to the common market, and since I was an Albino, everyone used to give me treats. It was great being pampered, but I also heard the women talking politics.” Wil later learned that those who frequented the market were perceived by the government as sympathizers or participants in the brewing conflict.

Early in 1979, when Wil was 13, the neighborhood around his home became noticeably more active in meetings and violence. “I was aware of the riots, workers complaining, everything was brewing,” Wil says. “At night you would hear the news that someone was kidnapped. Or a bank might be bombed, but we thought they were trying to get the money.”

The actual coup d’état that deposed the president, Carlos Romero (no relation to the archbishop), and that installed a civil-military junta, took place on October 15, 1979. The coup marked the beginning of the civil war which eventually, after several changes in national leadership, settled into a conflict between the FMLN and the Salvadoran army (including its aligned security forces), a conflict that would last 12 years. In the opening months of the war, the assassination of Archbishop Romero was, perhaps, the most widely-known murder, but on the night of March 31, one day after the archbishop’s funeral, Wil’s family became involved in the most tragic way.

Wil’s older brother, Rene, had joined the student organization attached to one of the guerrilla groups that made up FMLN. Although Wil’s family did not know until weeks later, Rene was kidnapped and executed by a para-military group on March 31. When the family did find out, Wil’s step-mother and sister left immediately for the United States. Wil, however, was not thinking of leaving at that moment. Despite the tragedy of his brother’s death and the escalating violence, he wanted to stay in order to finish high school and, hopefully, to marry his girlfriend Marina after graduation.

Wil’s plans progressed very well, considering the circumstances. He finished high school early, learned English, and got a job at a travel agency that had him working at the airport just outside of San Salvador. The job was welcome for two reasons: it allowed Wil to be as close to airplanes — his passion — as a legally-blind person could be and it was one of the most heavily-guarded sites in Sal Salvador, which meant he was unlikely to get shot at work. Getting to and from work, however, was another matter: “You could get on a bus to go to your job, and that will be the last time you’re on a bus. Fights break out in the middle of the street, and you get shot. The curfew is still on. And at night all you hear is the shooting.”

As the civil war continued to rage, the ordinary person on the street was getting pulled in to the conflict one way or another. “You were under pressure to join something,” Wil says. “Regular people didn’t want to fight, but there were no rules anymore. Everybody started killing everybody. If I had a relative in the military, I was a target. If I had a distant relative involved in the communist party or the guerrilla movement, I was involved. If you lived in a neighborhood, if you went to a church, you were labelled with whatever was happening there.”

By 1985, the polarization and violence had gotten so extreme that Wil began thinking he had no choice but to leave El Salvador. The change in mindset was caused not so much by preserving his own life, but by protecting the ones he loved: he and Marina had married and were expecting a child. “Really, I was thinking about moving anywhere,” Wil recalls. “But I decided to leave for the United States.”

Wil’s journey to the U.S. was similar in outline to the many well-known stories of Central American immigrants dramatized in movies like “El Norte” and novels like Odyssey to the North (by Mario Bencastro). The moment of decision, which is driven by fear and a longing for safety, is followed by a dangerous and stressful passage through unknown territories. Along the way, the travelers encounter people ready to exploit them for money or worse. The immigrants often travel by foot for much of the journey, foregoing the normal routines of daily life, such as regular meals and access to restrooms. Wil experienced all of this, and he had the added anxiety of protecting his wife — who was pregnant — and a young nephew who was travelling with them.

All three made it to the United States on August 23, 1985, and they moved quickly to Los Angeles where they were to meet a friend of Wil’s sister. The friend, Lupe, took the very tired travelers to her home, fed them and allowed them to shower, something they had not done in days. Lupe also took them shopping for new clothes. Wil says that he will never forget the movie he watched that first night in the U.S. at Lupe’s house: “It was the ‘Muppets Take Manhattan,’ and it was very interesting because it’s a movie about leaving your home and going somewhere else you don’t know. It was very representative of what was happening to us.”

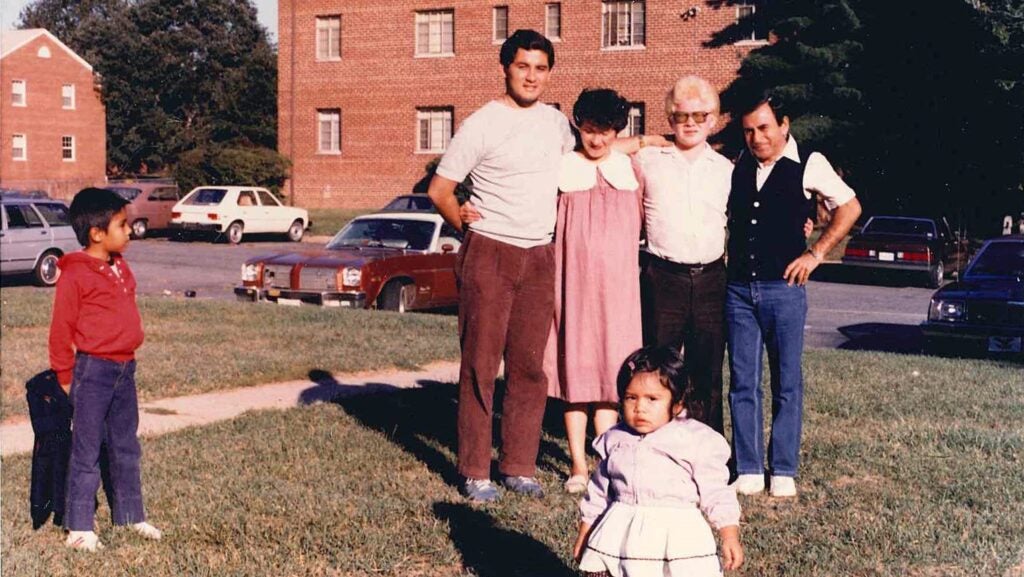

The first several years in the United States were a mix of joy and trials for Wil and Marina. Top on the list of joys was the birth of their daughter Gloria. Second to the top was the assistance they received from various organizations and churches open to helping immigrants in the 1980s. Through the compassion of friends and strangers, Wil and Marina were able to start building a life in the U.S. At first they lived with Wil’s sister until they were able to find an apartment for themselves. They went to work immediately: Wil cleaned office buildings at night and Marina assisted the beauticians at a salon during the day. Being self-sufficient and paying their own way was important to Wil. “I never wanted free things,” Wil says. “I just wanted a chance.”

Although Will counts coming to the United States as “the biggest blessing of his life,” he also suffered many trials as he made the effort to assimilate. “I thought that by me knowing English it was going to be really easy here, but I was wrong.” Sadly, for as many people who helped Wil and Marina, there seemed to be an equal number who treated them poorly and even threatened at times to call INS on them. “I didn’t understand,” Wil says. “We weren’t stealing anyone’s jobs. No one wanted to do what we were doing. We were working and trying to feed our families. But what we heard was, ‘you should just go back and die in your own country.’ That’s basically what they were saying.”

Nevertheless, Wil, through hard work and determination, was able to graduate from cleaning offices to building a career with Pan American World Airways, where he gained all the technical skills and knowledge necessary to become a software manager. Wil has been blessed, and he has contributed positively to the communities and workplaces of which he has been a part. “I can be an example of what can happen when you give a person some help, when you don’t put barriers on people, when you give them that opportunity,” he says.

Wil is quick to add that he is not for open borders, and he acknowledges readily the responsibility newcomers have toward their host country. Yet he is worried that a nation like the United States, which has always been known for welcoming immigrants and refugees, will take back its outstretched hand and refuse to help people when they need it the most. Considering the enormous contributions that immigrants and refugees have made for the benefit of the U.S., such an attitude bodes well for no one.

When asked what he would say to a person who thinks that he should never have come here, Wil says, “I hope that such a person is never in the position I was, where staying in their home meant facing possible death, not just for the person, but for their family too. I hope that person is never placed into a situation where they have to make that same decision.”